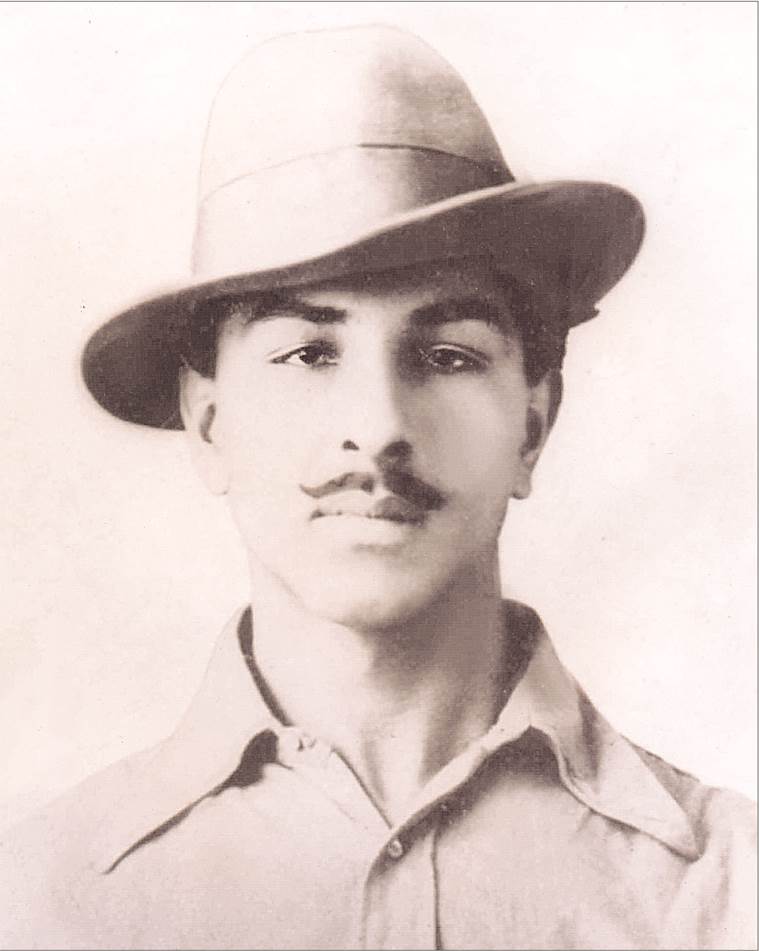

Eighty-five years after the hanging of Bhagat Singh, lawyers from India and Pakistan have joined hands to re-open, and overturn, the sham trial that led to his death.

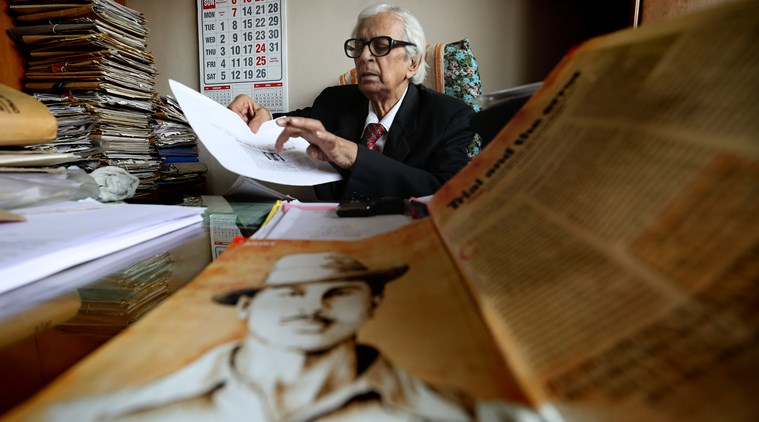

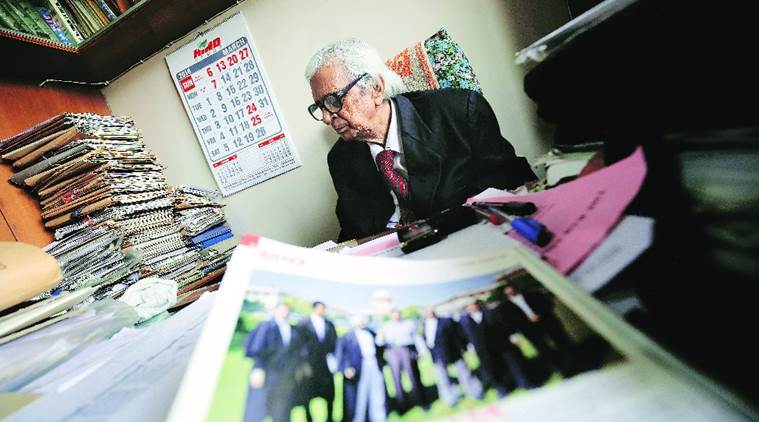

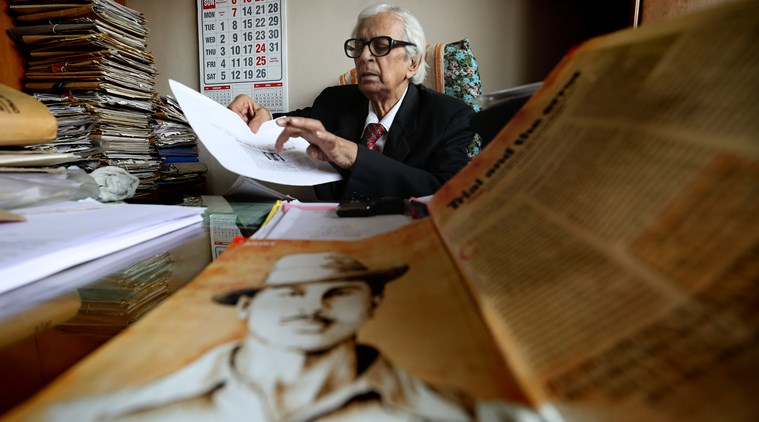

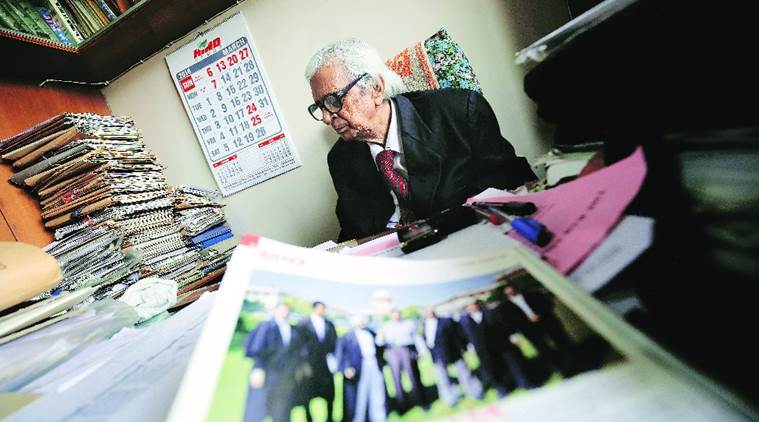

In a dark, poky room that constitutes his chamber in the new block of the Supreme Court, Delhi, Nafis Siddiqui, a 77-year-old criminal lawyer, has been preparing for a most unorthodox case for the last two years.

As part of his research, he has been reading up on cases where verdicts have been upended after long periods of time. He cites the case of George Stinney, a young boy, exonerated 70 years after his death by a court in US (in 2014), that found he was denied due process. Siddiqui points out another relevant trial; the ongoing legal battle between the British government and victims of Kenya’s Mau Mau emergency, who are demanding compensation 50 years after the events. “When it comes to infringement of fundamental rights, a delay in the matter is of no consequence,” he says.

With loose-flowing white hair, thick-framed glasses and oversized black coat, Siddiqui is an idiosyncratic figure. He pulls out a thick brown folder marked “Bhagat Singh”, with whom he has grown to be familiar through history books and family lore — Siddiqui’s father-in-law, Hasrat Mohani, a freedom fighter, communist and poet, credited for coining the slogan, “Inquilab Zindabad!”, had a great influence on the revolutionary. “I mostly handle cases of murder, and this is clearly a case of political murder,” he says.

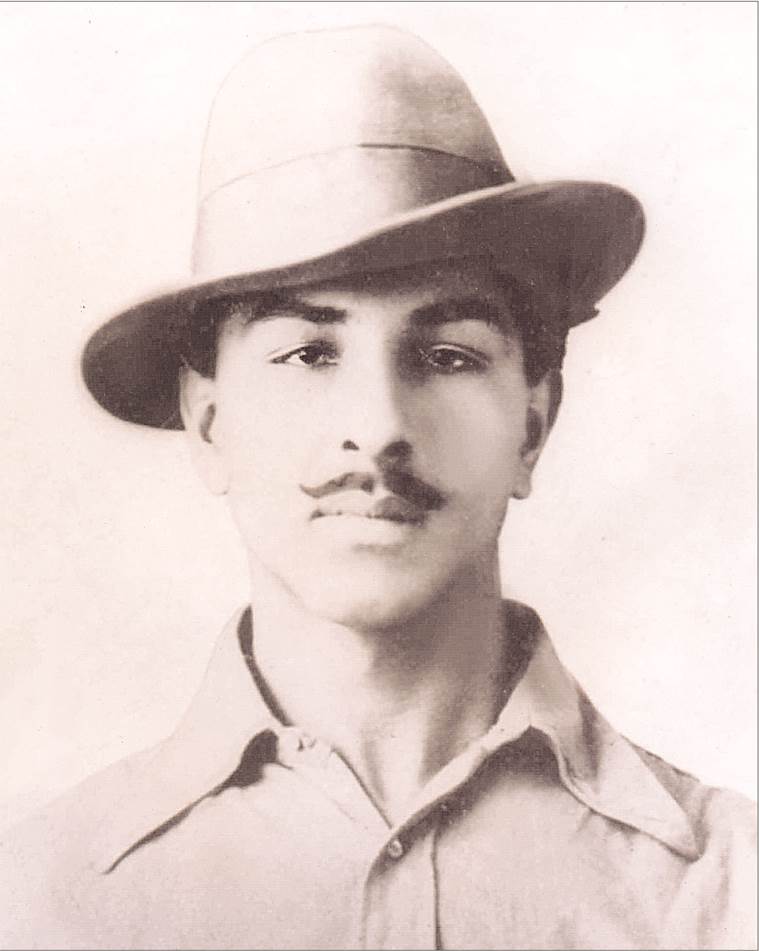

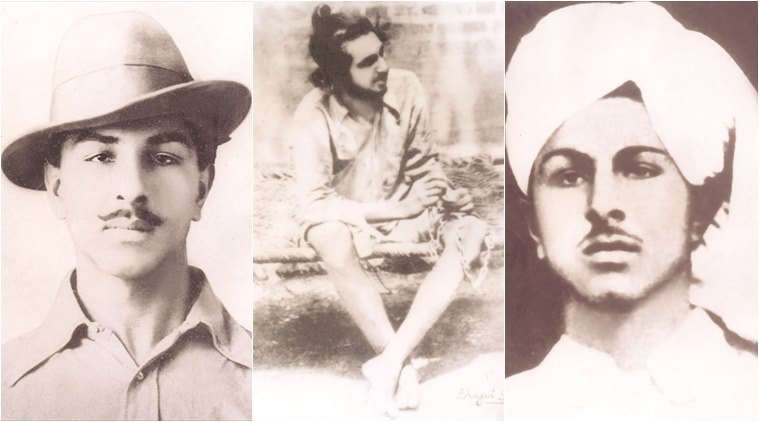

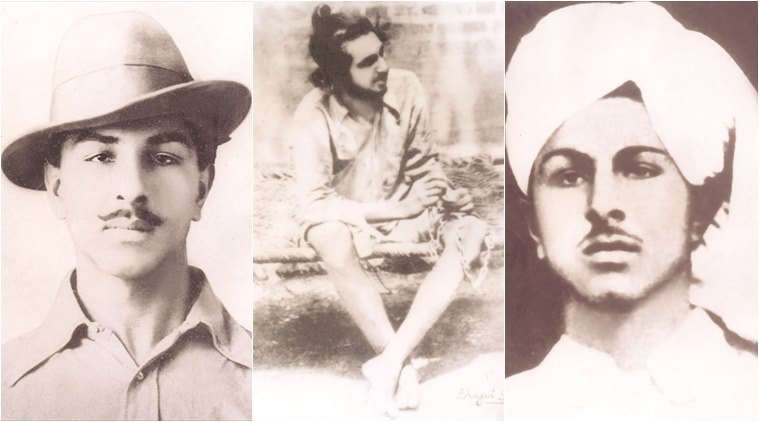

Eighty-five years after the hanging of Bhagat Singh, a lawyer from Pakistan is trying to pull off what is either an audacious attempt to change the course of history, or a fool’s errand. In 2014, Siddiqui was approached by Lahore-based Imtiaz Rashid Qureshi — who has been fighting a lone battle to prove the innocence of Bhagat Singh — to advise him on his case. Qureshi’s petition, which was filed at the Lahore High Court in 2013, seeks to reopen the case of the hanging of Singh and his compatriots, Sukhdev Thapar and Shivaram Rajguru, whose death anniversary will be celebrated on March 23 as Martyrs’ Day. In February this year, a two-member division bench in Lahore referred the case to a larger bench. For Qureshi, who argued that only a bench of three or more members could undo the decision of the three-member bench that awarded the death sentence in 1930, it was a moment of victory.

The first breakthrough came in 2014 when the court handed him a copy of the original FIR for the murder of British police officer John Saunders lodged at Lahore’s Anarkali police station in December 1928. The FIR does not name any of the three accused.

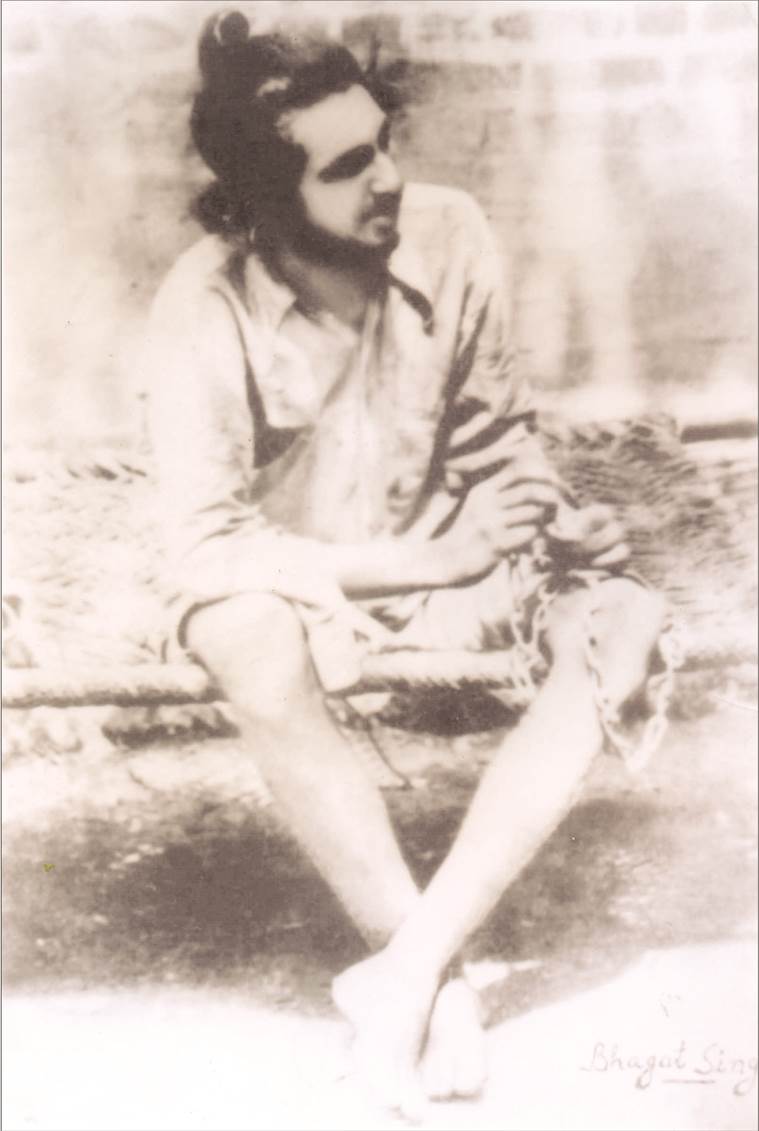

This is just one of the many discrepancies of the Lahore Conspiracy Case, which lasted for nearly two years and is universally recognised as a sham trial. As AG Noorani detailed in his book, The Trial of Bhagat Singh, from the lower court to the tribunal to the Privy Council, it was a judgment that represented a total compromise of the legal process.

The accused remained absent through the proceedings and remained unrepresented. Halfway through the trial, an Indian judge, deemed sympathetic to the accused, was removed from the tribunal. Many other rules of law were flouted. In a scathing editorial that appeared in April 1931, in the Marathi newspaper Janata, soon after the hanging, BR Ambedkar called out the hypocrisy of the British who manipulated the trial for political ends.

“We are demanding two things, that the British government, through the Queen, apologise to both our countries, and pay compensation to the families of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev,” says Qureshi over the phone from Lahore. Loquacious and deeply committed to the cause, he calls himself a “lover of Bhagat Singh” and runs a memorial in his name, the Bhagat Singh Memorial Foundation. “This is a case that unites the two countries and it proves that Pakistan, an

Islamic state, can also be liberal. Let’s not forget the Quaid-e-Azam was the only leader to have publicly defended him.” In a speech he gave in the Central Assembly in 1929, Mohammad Ali Jinnah had famously expressed his sympathy for the revolutionaries.

Qureshi’s pursuit has had a ripple effect in India. In Ludhiana, the descendants of Sukhdev Thapar have recently written to the Indian government, demanding a copy of the FIR and papers related to the judgment. Ashok Thapar, (a great-nephew, his grandfather was the younger brother of Sukhdev), who runs the Shaheed Sukhdev Thapar Memorial Trust, says, “We want government support to go to Lahore and pursue this case, or we will file an RTI. As his blood relations, we have a claim.”

More than perhaps the verdict, the reopening of the trial is crucial for another reason. There is renewed hope that the court will order the release of about 164 files related to the case, which are with the Punjab Archives in Lahore. They have been treated as “sensitive”, and no historian or researcher has ever been allowed to access them, says Ludhiana-based Jagmohan Singh, a researcher on Bhagat Singh. He also happens to be Bhagat Singh’s nephew, born to his sister Bibi Amar Kaur. But, unlike the sustained campaign around the declassification of the

Netaji files, these files have been neglected. Yet, they are a crucial part of setting the record straight.

“The trial may or may not change history, but it’s the right of the people to know what happened, and those files will help us get there,” says Shantanu Rajguru, a great-grandnephew of Shivaram Rajguru. The family lives in Pune and is currently putting together a biography on the revolutionary. It was Rajguru, known as the marksman of the group, who fired the shot that killed Saunders. But Rajguru, like Sukhdev (who was in charge of coordinating the operation to avenge the death of Lala Lajpat Rai), has been reduced to a footnote in history, believes Shantanu. The descendants of Sukhdev believe that the retrial should not be held in the name of Singh alone.

*****

Apart from the context of historicity, the trial is significant as a measure of the democratic struggle in Pakistan being led by the civil society. The effort to reinstate Bhagat Singh as an icon has gathered force in recent times, as he has emerged as a symbol for the secularists in their battle against illiberal forces. Singh belongs to the pantheon of heroes of the Indian subcontinent. He is venerated in Punjab where he was born. “The PIL is an important political and historical development in a country and a region where history is often distorted in textbooks, held hostage to nationalist expediencies and heroes like Bhagat Singh are simply whitewashed or relegated to a footnote,” says Raza Naeem, a social scientist and activist from Lahore, over an email interview.

While there is no official celebration of his martyrdom day in Pakistan, every year, on March 23, there is a gathering of activists at Shadman Chowk, next to Lahore Jail, where he was executed. Since 2001, there has been a movement demanding Shadman Chowk be renamed Bhagat Singh Chowk. The government agreed a few years ago, but capitulated when Islamist groups objected to the icon on grounds of his religious identity. In a conciliatory move last year, the government announced a package of Rs 8 crore, for the restoration of his ancestral house in Faisalabad district.

“I have attended the annual gathering at the chowk for a few years and every year, the movement has grown,” says Haroon Khalid, Pakistani author and journalist. “It is now part of the broader debate that seeks to widen the horizons of Pakistani nationalism by incorporating non-Muslim heroes as well. Another interesting dynamic of this movement is that it also comes at a time when the Pakistani state actively wants to re-project itself as a liberal secular state. There has been particular focus on the protection and promoting of Sikh heritage in the country. Bhagat Singh is seen in that broader framework of this Sikh heritage,” he says.

*****

(The other aspects touched in the original article are not subscribed to or agreeable with me. It would be a narrow approach to stifle the Patriotic actions of the Revolutionaries under the Colonial Rule to a set of political isms. It is also equally wrong and disruptive to equate those Revolutionaries in the real sense to the present ongoing events involving a few misguided, politically motivated individuals.)

SOURCE -

http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/freedom-fighter-bhagat-singh-inquilab-zindabad-supreme-court-nafis-siddiqui-george-stinney-hasrat-mohani-in-defence-of-a-revolutionary/#sthash.WNn5MgTv.dpuf